In Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’, why are the men so self-centred and the women so meek? In this blog, Professor Richard Marggraf Turley from Aberystwyth University explores gender and toxic masculinity in the novel.

Just as Victor’s creature is constructed using parts from several male bodies, the novel itself is stitched together from tales told by men. Each male narrator is ‘extreme’ in some way – each strives, in Victor’s words, to ‘be more than men’. The framing narrative is related from the perspective of intrepid arctic explorer Robert Walton in letters to his sister, Mrs Margaret Walton Saville. Mediated (re-voiced) through Walton’s account, the megalomaniacal Victor Frankenstein gives the history of his own anguished relationship with his vengeful creation, who is also given substantial space to describe his titanic sense of betrayal and mistreatment at Victor’s hands. By contrast, the novel contains few female characters. Margaret, the recipient of Walton’s letters and journal (and in a sense, Frankenstein’s first reader), isn’t heard from at all. Justine and Elizabeth seem to exist primarily as victims of male violence. Similarly, the female mate whom Victor begins to build is violently dismembered, literally torn limb from limb in one of the novel’s most shocking scenes.

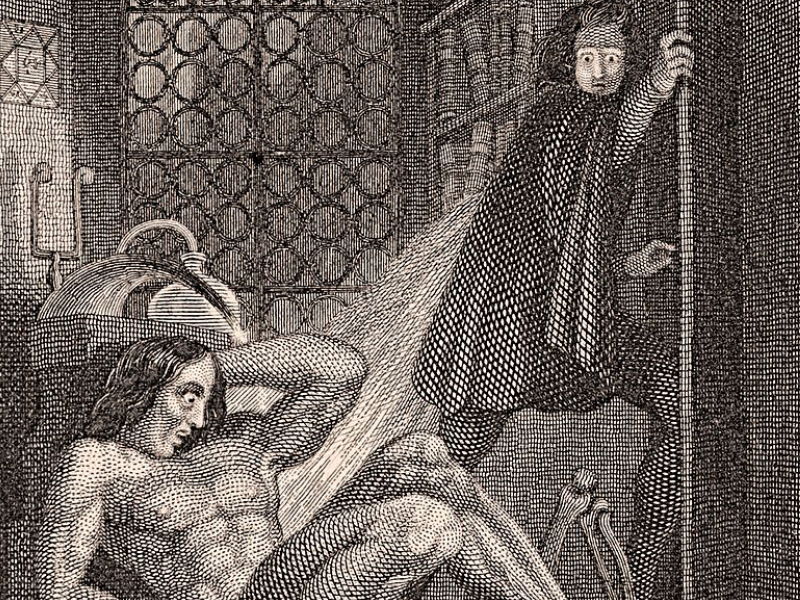

Why are Mary Shelley’s women given so little voice in the novel, so little ‘agency’? After all, Mary Shelley was the daughter of proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, whose A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) was one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. One way of answering that is to say that, surrounded by ‘heroic’, self-centred men such as her husband Percy Shelley, Lord Byron and her father, the philosopher William Godwin, Mary Shelley sets out to write a critique of Romantic masculinities. In particular, she focuses on aggressive, overreaching men with a fear of physical intimacy. Consider the key scene in which the creature appears at Victor’s and Elizabeth’s wedding bed. The novel’s frequent use of doubling allows us to see the creature’s manifestation here as an expression of Victor’s sense of masculine inadequacy. In a psychological sense, Victor has ‘summoned’ his monstrous projection, his eight-foot-tall doppelgänger, to stand in for him on his wedding night to do what he cannot do, namely ‘consecrate’ his marriage – with violent consequences. All three male protagonists, even far-flung, secluded Walton, are undercut by the novel, revealed to be both self-destructive and toxic for all those around them – particularly women.

In terms of gender and masculinity, then, Frankenstein is a complexly situated, complexly self-aware, novel. It is as much ‘about’ female experience of male violence as it is about the eponymous creature’s own struggle with prejudice, neglect and rejection. The novel is as embedded in the larger anxieties and struggles of the ‘heroic’ Romantic age of intellect and discovery as it is focused on Victor’s own self-doubts and agonies. It is as concerned with the importance of loving family structures as it is keyed into the danger of tyranical male ambition. Finally, it is a novel as rooted in Mary Shelley’s personal experiences of overbearing, destructive masculinities as it is in the ‘autobiographies’ of its three tortured, self-tormented protagonists.