Yesterday’s thrills, today…

Professor Richard Marggraf Turley talks about our obsession with self-tracking and how it inspired him to develop ‘The Vortex’ – a machine that analyses our reactions to sublime and Gothic works.

‘I’ve got chills, they’re multiplying,’ sang John Travolta, dancing off with Olivia Newton John at the end of 1978’s musical spectacular, Grease. Travolta – or rather his screen persona, Danny Zuko – could almost be an early advocate of the ‘Quantified Self’ movement, the name adopted by those who use biometrics to capture as much information as possible about physical aspects of their daily life. As well as temperature (chills, flushes), pulse rate skin conductivity, blood-sugar levels, and most recently mood, can all be tracked, and analysed for trends. For some self-quantifiers – or ‘body-hackers’ – the aim is to live happier, healthier, more productive lives. Others are simply fascinated by the data-streams generated by their own bodies. At any rate, these days if you want to know how many chills you’ve got, and precisely how quickly they’re multiplying, you only need glance at your smart watch or health-and-fitness phone app.

The greaser, Danny, was by no means the first person to notice physical changes taking place in his body in response to a strong stimulus (in his case, a black-clad ONJ). We can trace a fascination with the body’s reaction to visual and imaginative stimuli at least as far back as the Romantic period in Britain, to the 1780s–1820s. In this period, a popular new modality had emerged in art and literature: the Gothic. It aimed to produce emotionally vertiginous shocks and thrills; sensations of any kind, in fact, so long as they put the viewing subject – the ‘Self’ – at the centre of the experience. ‘O for a Life of Sensations!’, declared the poet John Keats, articulating an important aspect of the spirit of the age.

The greaser, Danny, was by no means the first person to notice physical changes taking place in his body in response to a strong stimulus (in his case, a black-clad ONJ). We can trace a fascination with the body’s reaction to visual and imaginative stimuli at least as far back as the Romantic period in Britain, to the 1780s–1820s. In this period, a popular new modality had emerged in art and literature: the Gothic. It aimed to produce emotionally vertiginous shocks and thrills; sensations of any kind, in fact, so long as they put the viewing subject – the ‘Self’ – at the centre of the experience. ‘O for a Life of Sensations!’, declared the poet John Keats, articulating an important aspect of the spirit of the age.

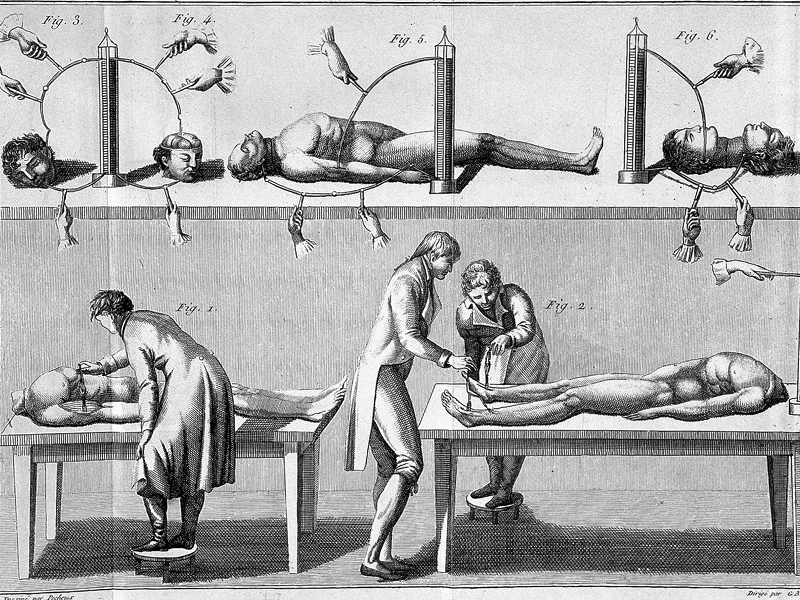

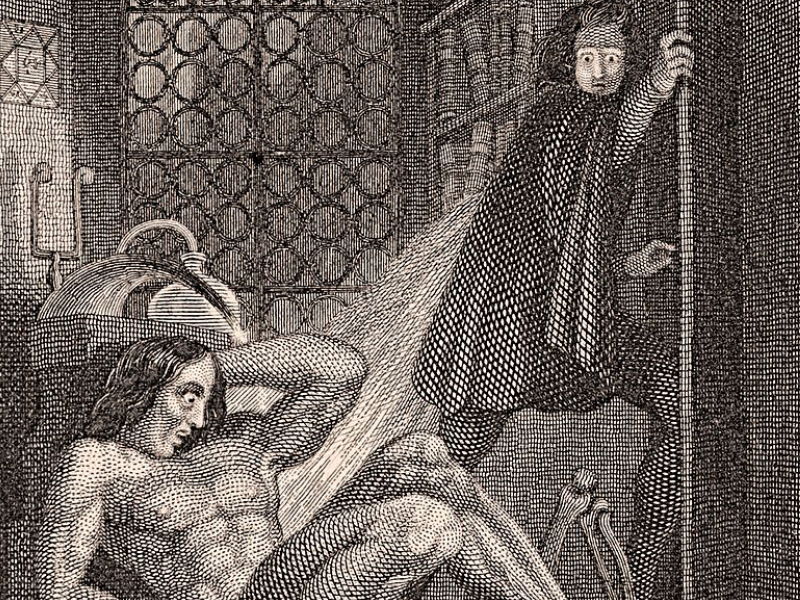

Romantic writers and painters were convinced that ‘sublime’ art and nature – anything that conveyed massiveness, volume, the all-encompassing – provoked a distinctive physical and emotional signature (terror), which others could ‘read’ in the form of a fevered brow, breathlessness, or flushed cheeks. A craze developed among members of the public eager to experience these changes for themselves, moreover in a self-aware manner. Enthusiasts would slog for miles to stand in exactly the right spot to get the full effect of a dizzying precipice, or gaze up at a thunderous waterfall, or contemplate the dark ruins of a medieval abbey. At home, candlelit connoisseurs would turn the pages of the latest gothic shocker to gasp at the nefarious schemes of a priapic monk or uncanny doppelgänger, or fall headlong and senseless into an engraving of towering waves, and black, depthless, watery vortexes. The goal was to overwhelm the senses, to annihilate ‘Self’. In Dany Zuko’s terms, it was all about ‘losing control’ – while loving every minute of it!

Perhaps Romanticism can lay claim to the first (fictional) Quantified Selfer. In 1816, Mary Shelley drafted her famous gothic novel, Frankenstein, while holed up on the shores of Lake Geneva with the self-exiled Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and Byron’s physician, Dr Polidori – author of the The Vampyre (1819), the book that spawned a thousand TV series from Buffy to The Strain. Mary’s classic not only generated chills in its readers, but foregrounded the very issue of how nerves and sinews – the body’s sensorium, or sensing apparatus – came together in the first place. Frankenstein’s creature, obsessed with how he was put together, with the relation between body, mind and emotions, is both proto-embodiment and practitioner of bio-hacking.

Perhaps Romanticism can lay claim to the first (fictional) Quantified Selfer. In 1816, Mary Shelley drafted her famous gothic novel, Frankenstein, while holed up on the shores of Lake Geneva with the self-exiled Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and Byron’s physician, Dr Polidori – author of the The Vampyre (1819), the book that spawned a thousand TV series from Buffy to The Strain. Mary’s classic not only generated chills in its readers, but foregrounded the very issue of how nerves and sinews – the body’s sensorium, or sensing apparatus – came together in the first place. Frankenstein’s creature, obsessed with how he was put together, with the relation between body, mind and emotions, is both proto-embodiment and practitioner of bio-hacking.

The consumer face of self-tracking today – think biometric wristbands like Apple Watch, Android Gear, Nike+ FuelBand, Jawbone and Fitbit – was first developed in the decade in which Grease topped the billboard charts. Hardly portable, the technology was used mainly by researchers who recognised the potential of analysing personal data to correlate useful information about lifestyle. Only in recent years, with the miniaturisation of components, has the Quantified Self movement entered the mainstream. Most people who use smart watches to ‘drill down’ into their jogging stats, sleep patterns and heart rate probably don’t think of themselves as bio-hackers anymore, which suggests that self-analysis, or self-surveillance, is fast becoming routinised. Indeed, few of us even stop to think about the possible dangers of allowing so much information about our fitness or daily routines to be mined by third parties. Quite aside from issues of personal privacy, there may be companies out there looking for trends in our health data we’d rather they didn’t know about.

For Living Frankenstein, members of the public will be invited to enter – if they dare – The Vortex, a dark enclosure in which they’ll be shown Gothic images. While they experience (we hope) an annihilation of Self, I will be using a package of specially built biometric instruments to measure any changes in pulse rate, and counting chills (multiplying, or otherwise). We’ll also be discussing the wider social and political implications of biometric wearables and other self-tracking technologies.

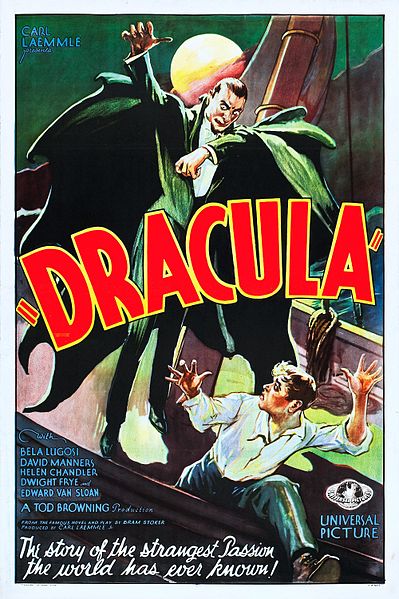

The 1931 Frankenstein was made on the back of the success of Universal Pictures’ Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931) starring Bela Lugosi in the lead role. Similarly, in 1993 Francis Ford Coppola released his lavish Bram Stoker’s Dracula—an adaptation filled with gothic trimmings and packed with star performances. Kenneth Branagh’s high profile adaptation Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) follows the release pattern of its most lingering cinematic forbears. Branagh’s adaptation is a film that abounds with references: the film refers to a variety of cultural and literary texts, it refers to Mary Shelley’s novel, and the film’s own cinematic antecedents. An example of this is the film’s depiction of the birth of Victor’s brother William, during which their mother dies. This scene of William’s birth does not occur in Shelley’s novel—this is only in the 1994 adaptation. This particular sequence is part of how the film tries to position itself as part of the horror genre, but it also parallels Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s own birth, after which her mother Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin died. Scenes like this, which allude to a famous author’s personal life, are one of the ways in which screen adaptations make use of more than just the source text.

The 1931 Frankenstein was made on the back of the success of Universal Pictures’ Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931) starring Bela Lugosi in the lead role. Similarly, in 1993 Francis Ford Coppola released his lavish Bram Stoker’s Dracula—an adaptation filled with gothic trimmings and packed with star performances. Kenneth Branagh’s high profile adaptation Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) follows the release pattern of its most lingering cinematic forbears. Branagh’s adaptation is a film that abounds with references: the film refers to a variety of cultural and literary texts, it refers to Mary Shelley’s novel, and the film’s own cinematic antecedents. An example of this is the film’s depiction of the birth of Victor’s brother William, during which their mother dies. This scene of William’s birth does not occur in Shelley’s novel—this is only in the 1994 adaptation. This particular sequence is part of how the film tries to position itself as part of the horror genre, but it also parallels Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s own birth, after which her mother Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin died. Scenes like this, which allude to a famous author’s personal life, are one of the ways in which screen adaptations make use of more than just the source text.